Sapan News Two sets of convicts were released from jail this year in India: Rajiv Gandhi’s assassins and men who had been convicted for the gang rape of Bilkis Bano, then pregnant, and for the murder of 14 of her family members including her three-year-old daughter, in Gujarat, 2002. The first pardon cannot be used to justify the second, as there are critical differences between the two.

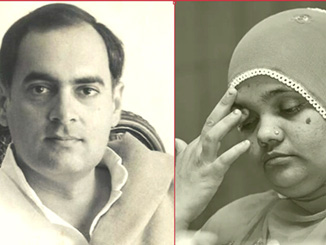

The Indian Supreme Court’s premature release of the six remaining convicts in the Rajiv Gandhi assassination case was not unexpected. The court had already set a precedent by ordering the release of A.G. Perarivalan, who had been incarcerated for over 30 years in the same case.

The suicide bombing that killed India’s prime minister Rajiv Gandhi in Tamil Nadu, 1991, was planned in revenge for sending the Indian Peace Keeping Force to Sri Lanka against Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam.

A popular Tamil sentiment in India favoured the release of the convicts, who are all ethnically Tamil – two Indian citizens, and four Sri Lankan. Tamil political parties have also supported the release of the convicts. In September 2018, the previous All India Anna Dravida Munnetra Kazhagam government in Tamil Nadu passed a cabinet meeting resolution calling for the release of these convicts. The current Dravida Munnetra Kazhagam government has continued to judicially pursue the matter of their release.

Rajiv’s family – widow Sonia, daughter Priyanka Vadra and son Rahul – have not objected to the convicts’ release. In fact, Sonia Gandhi played an important role in getting the death sentence of four convicts commuted to life term, including the only woman among them, Nalini.

Priyanka even visited Nalini in Vellore Jail and is reported to have wept with her. Nalini has described Priyanka as an angel and prayed for her wellbeing.

While the Congress Party has opposed the Supreme Court’s decision to order the premature release of the convicts, the Gandhi family has tacitly condoned the release by staying silent on the matter. This demonstration of large-heartedness comes as a welcome relief and stark contrast at a time when the politics of religious nationalism are fostering hatred and vengeance.

Some instances in recent history come to mind where the victims’ families have pardoned the perpetrators. Gladys Staines pardoned those who killed her husband, Australian missionary Graham Staines, and their two sons in Odisha.

Mohanda Gandhi’s granddaughter, Ela Gandhi, a peace activist and former parliamentarian in South Africa, holds no grudge or wishes any vengeance upon those who shot and killed her son at his home in South Africa in 1993, as she told me in a private conversation some time ago.

While strongly condemning all forms of killing and violence, she believes that it is only when perpetrators of violence understand and appreciate the injustice and inhumanity of their act of violence will they change and not commit such offences again.

“This realisation and change does not necessarily happen through condemnations, punishment and incarcerations” but “through a process of learning, conscientising and education,” she confirmed recently over email.

Such forgiveness requires elevating human consciousness to a high moral level. It is far easier, and more common, to pursue revenge after a grave crime.

There is no room for capital punishment in a civilized society. It is better to attempt to reform the convicts, or rather help the convicts reform themselves. If possible, there could be facilitation of some kind of reconciliation between perpetrators and their victims or family members – such as the concept of restorative justice popularised by the Truth and Reconciliation Commission after Nelson Mandela took charge in South Africa.

Unlike retributive justice which is based on vengeance and punishment, the restorative justice process allows perpetrators to seek amnesty after being made to understand the trauma and pain of the victims or their families. The hope, as Ela Gandhi says, is that they will then “be remorseful and will change and not commit such offences again”.

As a parliamentarian in South Africa, she herself has been involved in the process of promoting restorative over retributive justice, taking forward the vision of Bapu, her grandfather Mahatma Gandhi.

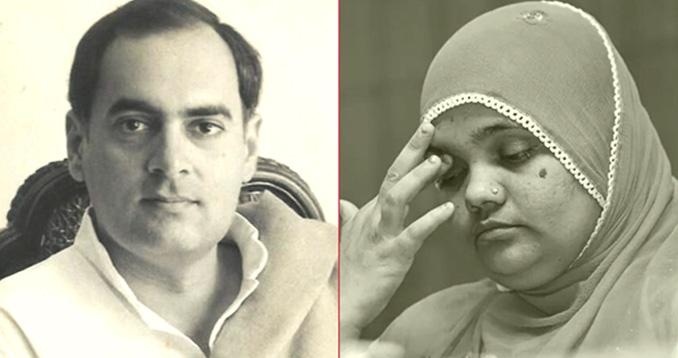

There are some critical differences in the release of convicts in the Rajiv Gandhi assassination, and the 11 convicts released this past August in the Bilkis Bano case:

– Firstly, it was the judiciary that took the decision to release convicts in the Rajiv Gandhi assassination case. In the case of Bilkis Bano, the government (Home Ministry) ordered the release, following a recommendation by a Gujarat government committee. The committee, headed by a District Collector, comprised five government officials: the Superintendent of Police, the jail superintendent, a district judge, a social security officer and two legislators from the ruling BJP party. The move may also again rake up the Hindu-Muslim issue ahead of the upcoming Gujarat elections.

– Secondly, the convicts in Rajiv Gandhi assassination case had already spent over 30 years in jail. In the Bilkis Bano case, the convicts, sentenced 14 years ago, have already been out on parole and furlough for thousands of days each.

– Third, there is popular Tamilian sentiment backing the Supreme Court’s decision to prematurely release convicts in the Rajiv Gandhi case, although this support may well be of a sub-nationalism variety at variance with the national sentiment given that a prime minister was killed. On the other hand, only a handful of hardcore BJP-RSS cadres support the decision to release convicts in the Bilkis Bano case.

– Last but most crucially, the Rajiv Gandhi assassination convicts have been set free more or less with the concurrence of his family. These released convicts pose no threat to the Gandhi family, which has in fact pardoned them. This is clearly not the case with the convicts in the Bilkis Bano case. Since the convicts’ release, many Muslim families in the area feel threatened, and Bano and her family fear for their safety.

The release of the Bilkis Bano case convicts has left the victims vulnerable. The perpetrators in this case have exhibited no remorse for their crime. Right-wing Hindutva groups feted them with garlands and sweets when they emerged from Godhra sub-jail, celebrating criminals as heroes.

Ruling party member of the legislative assembly CK Raulji, a member of the committee which recommended the release of the convicts, justified the decision by terming some of them as ‘virtuous Brahmins.’ He plans to contest the upcoming Gujarat elections while senior politicians from his party have been made to withdraw from the contest.

The message being sent out is ominous. What kind of society do we wish to create where, if victims and their families belong to a certain religion or class, they must be prepared to live with the perpetrators of crimes against them roaming free?

The release of convicts in the Bilkis Bano case sets a bad example of remission of a sentence. It must be undone.

The writer is an educator and peace activist in Lucknow, a recipient of the 2002 Ramon Magsaysay award. He has organised several peace marches for better relations between India and Pakistan and for communal harmony in India. He is General Secretary of Socialist Party, India. Email: ashaashram@yahoo.com.

This is a Sapan News syndicated feature available to use with credit to Sapan News Network.

Leave a Reply