Noted journalists and women’s rights activists from Afghanistan and the diaspora came together to discuss the blatant ‘erasure’ of women from Afghan public life, and appealed to the international community to take action before it is too late.

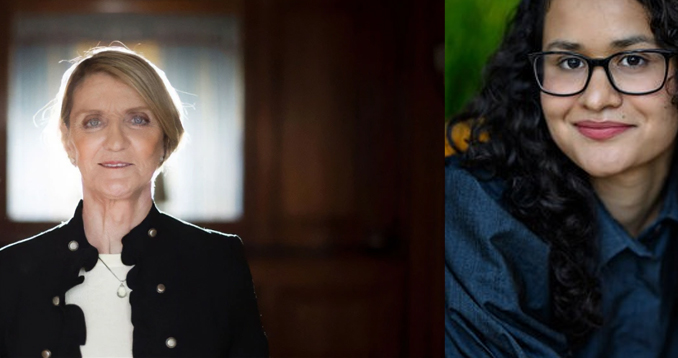

By Apoorva Gairola

The situation in Afghanistan today is “a lot worse than apartheid,” says human rights activist and Nobel Peace Prize nominee Mahbouba Seraj.

Speaking at a recent discussion on ‘gender apartheid’ in Afghanistan Seraj stressed that the people in Afghanistan have to be strong because “they have to live the reality”. She argued that Afghans should not be thought of as “those people” by the rest of the world, and that “if we don’t talk about it, it will affect women all over the world”.

Seraj also pointed out that the inaction or reaction of the world should not result in destroying 40 million people and her country.

The UN defines gender apartheid as “the economic and social sexual discrimination against individuals because of their gender or sex. It is a system enforced by using either physical or legal practices to relegate individuals to subordinate positions.” Despite the heinous nature of it and despite calls from various feminist organisations worldwide, gender apartheid is not considered an international crime.

The discussion was the second of the Southasia Peace Action Network’s ‘Country Focus’ series, and its 21st monthly webinar. Held on September 24, 2023, in collaboration with US-based nonprofit Tasveer, the session explored the condition of Afghanistan’s women following the Taliban’s return to power in August 2021 after then President Ashraf Ghani fled the country and American troops withdrew.

The objective of the online discussion, which featured leading women’s rights activists and journalists, was to create global awareness, promote open dialogue and develop solutions.

The human-rights situation in Afghanistan is gruesome, particularly for women whose fundamental rights are being restricted to the point of absolute deprivation. They are banned from public spaces, studying and working.

Panelists included journalists Farida Nekzad and Kreshma Fakhri as well as author Sola Mahfouz and Sunita (name changed for safety reasons) who lives in Kabul and has worked on education, empowerment and rights protection. Afghan women’s rights activist and peacebuilder Wazhma Frogh moderated the panel discussion while Canadian journalist and former news director of Associated Press for Afghanistan and Pakistan offered concluding remarks.

“This is not the end of Afghanistan,” asserted Wazhma Frogh in her introductory remarks, pointing out that much progress had been made after 2004, following two decades of conflict after the Soviet invasion.

“The next two decades were about teaching people, building institutions, constitutional recognition of the equality of men and women, and election laws,” Frogh added.

Media and journalism flourished, with thousands of women joining the thriving industry with dozens of media institutions. All that changed after 2021.

Kreshma Fakhri detailed the plight of women journalists after the Taliban took over. She said that almost 80% had been forced to leave their jobs, according to a report filed by Reporters Without Borders. Women journalists are not allowed to work in most parts of Afghanistan. Many have faced threats, been physically and/or sexually assaulted, and even forced into marriage.

Anxiety turns to depression, hope becomes hopelessness when no way out is in sight. “Amidst all the difficulties and restrictions, women are feeling hopeless about escaping them. This leads them to opt for suicide as a solution,” Fakhri said.

Gender apartheid is not just about Afghanistan but an issue of global importance, said senior journalist Farida Nekzad, arguing for national and international cooperation “so the international community comes forward to accept the crimes of Taliban as gender apartheid.”

“If that does not happen, this is like a virus and can spread to other countries,”’ she warned.

There are now almost no women in workplaces in Afghanistan. The Taliban hold that women can work in strictly segregated environments only, and until this is facilitated, they cannot step out of their homes.

After the fall of the Taliban in 2001, scientist Sola Mahfouz was “one of the first girls in her neighbourhood to go to school”. Her education was cut short in 2007 as the Taliban began making their presence felt again, threatening girls who attended school, she added.

The co-author of Defiant Dreams: The Journey of an Afghan Girl Who Risked Everything for an Education (Penguin Random House, 2023), she talked about how she initially hated school. She is now a researcher at Tufts University in the Boston area, USA.

When the world around her ceased to make sense after girls were forced to stay at home, it was her grandfather, who was self-taught, who encouraged her to learn English.

“Fortunately, we had the internet,” and that she also learnt math through the Khan Academy, she said, observing that her situation reflected that of many girls in Afghanistan.

Sunita, joining from Kabul, explained the current state of affairs, “Working women in the government sector have been sent home indefinitely except for public health workers and some teachers. If you walk the streets of Kabul you’ll find lots of women and children begging in the streets.”

“Afghanistan has always been about politics but never about the Afghans and that has not changed,” observed journalist Kathy Gannon, who has worked for almost four decades in the region and is the author of I is for Infidel: From Holy War, to Holy Terror, 18 Years Inside Afghanistan (2005).

“The international community has to accept responsibility,” she said, stressing that their presence in Afghanistan would create room for discussion and empower Afghan women.

“In 2007, Sola had to stop school because of threats and the international community continued to tell lies about what was really going on. There was a price to that which is being paid today because of not addressing so many issues at a time when it was possible to address them,” she said.

The Taliban are not a monolith, noted Gannon. “There are different voices that can be amplified,” she said, adding that men have to be engaged “and their voices have to be amplified alongside the women’s.”

Despite the dire situation, the panelists held out hope about the future.

“We are not going to always be where we are and we are not going to be not listened to,” insisted Mahbouba Seraj. “I can promise you that because the world is listening.”

“Millions of struggling women and girls in Afghanistan dream that maybe tomorrow they will be able to go to school. Even inside the four walls, they find ways to continue by learning something that enables them to keep the hope alive,” said Frogh.

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit. Ut elit tellus, luctus nec ullamcorper mattis, pulvinar

Afghanistan is the only Islamic nation to ban women from work and education. Since Taliban justify their actions in the name of religion, other Islamic nations could collectively intervene, pointed out participants in the webinar. Other countries in the region could also have a positive impact.

Other potential solutions involve creating global awareness, fostering dialogue, and building institutions that bring communities together.

Apoorva Gairola is a psychology professional and former journalist from India who is passionate about women’s and gender issues. This is a Sapan News syndicated feature.

Leave a Reply